From the Naxos Blog: F sharp major, of all keys!

August 06, 2021Western composers uniformly embraced the system of tonality for some two centuries, until it found itself challenged by a radical alternative system called atonality around the year 1900. The more abrasive sounds thrown up by atonality certainly gave the status quo a run for its money, while never actually totally replacing it.

Source: usercontent1.hubstatic.com

Tonality allowed composers to write their music in 24 different keys: 12 that sounded brighter (major keys) than the other 12 (minor keys). The names of the keys derived from the 12 names given to the black and white notes on, say, a piano, the pattern of which clearly replicates itself from the bottom to the top of the keyboard. C major employs none of the black piano keys, and C will be the dominant note in the music, to which the rest are anchored and subservient. Beginner pianists will know the mounting challenge of being in a key where increasing numbers of those black notes are used, known as sharps and flats. Mid point between one C to the next is the note F sharp, and F sharp major uses 6 sharps, of which only 5 relate to black notes; the sixth is a white one. Confusing, isn’t it?

Composers throughout the time of this system of tonality fancied writing sets of pieces that roamed through every single one of those 24 available major and minor keys. I’ve dipped into those collections to present a chronological progression of excerpts that reflect a corresponding progression of styles, all of them in that key of F sharp major (or G flat major, which sounds the same but is written down differently—sorry to add to the confusion!).

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) paired a Prelude with a Fugue 24 times, using all the major and minor keys, and then repeated the exercise to produce his celebrated ‘48’. Here’s the Fugue in F sharp major from the first of those sets, performed on the harpsichord.

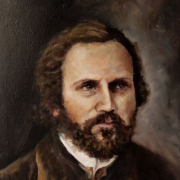

Pierre Rode was born in Bordeaux, France in 1774. He became the star pupil of Giovanni Battista Viotti, the foremost violinist of the day and founder of the modern French violin school. Rode’s ‘breakout’ year was 1792, when he performed six times between 1 and 13 April, including two concertos by Viotti. During the next sixteen years Rode lived the life of a travelling virtuoso. He composed almost exclusively for his own instrument and his 24 caprices en formes d’etudes for solo violin remain among the most studied violin pedagogical works ever written. Here’s the Caprice No. 13 in G flat major.

Born near Warsaw, the son of a French émigré and a Polish mother, Fryderyk Chopin (1810–1849) won early fame in the relatively limited circles of his native country before seeking his fortune abroad, in Paris. He was able to establish himself as a pianist and as a teacher of the piano, primarily in fashionable society. His compositions, principally for the piano, make a remarkable use of the newly developed instrument, exploring its poetic possibilities while generally avoiding the ostentation of the Paris school of performers. From his set of 24 Preludes, Op. 28, here’s the Prelude No. 13 in F sharp Major.

Born around the same time as Chopin, but outliving him by nearly four decades, is the French pianist/composer Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813–1888). At one time his name was associated with those of Chopin, Liszt, Schumann and Brahms as one of the greatest composers for the piano in the age that followed the death of Beethoven. At the Paris Conservatoire he was a piano pupil of Joseph Zimmermann, future father-in-law of Gounod and teacher of Bizet and César Franck, and won considerable success as a child prodigy, exciting even the admiration of Cherubini.

The first half of his life had its ups and downs. He gave a concert in May, 1849, that was to prove his last for the next 25 years. Isolating himself from the general musical life of Paris, Alkan continued in the following years to teach and, intermittently, to compose, living a hypochondriac bachelor existence of obvious eccentricity.

Written over the previous fifteen years, Alkan compiled his Esquisses (Sketches) in 1861. Like Bach, he had written two sets comprising all the major and minor keys, leading to his original title of 48 Motifs. Here are the two short items occupying the key of F sharp major: Le frisson (The thrill) and Debut de quatuor (Beginning of a quartet).

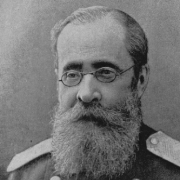

To nudge us into the 20th century I’ve selected a piece by a Russian composer who was a member of the group of Russian nationalist composers known as The Mighty Five: César Cui (1835–1918). Balakirev, Borodin, Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov were the other four; today, Cui is all but forgotten. His reputation for being the weakest link in the group would certainly seem to be confirmed by Tchaikovsky’s observation that “By nature, Cui is more drawn towards light and piquantly rhythmic French; but the demands of the ‘invincible band’ which he has joined compel him to do violence to his natural gifts and to follow those paths of would-be original harmony that do not suit him.”

From Cui’s 25 Preludes, written in 1903, here’s the Prelude in F sharp major: Andante.

For my final three selections of music written in the century that followed that piece by Cui, we move to Finland, back to Russia and then to the UK.

Born on the western coast of Finland, Selim Palmgren (1878–1951) was undoubtedly one of the most performed Nordic composers as regards piano music. His works were widely performed by some of the greatest pianists of the era, and made available by well-known music publishers both in the US and in Europe. The youngest of ten children, Palmgren was born into a family that was passionate about culture, which no doubt nurtured young Selim’s goal of becoming a professional musician. Coincidentally, the same evening Palmgren arrived in Helsinki in 1895 to study music, the acclaimed pianist Busoni was giving a recital. Palmgren was totally blown away by the musical experience and felt that his destiny had been sealed.

Palmgren’s 24 Preludes, Op. 17 is his largest cycle for piano and a rarity in Nordic piano literature. We can hear Prelude No. 19, titled Fågelsång (Bird Song), naturally written in the key of F sharp major and perhaps even more ‘naturally’ devoid of a time signature, suggesting the flighty freedom inherent in the title.

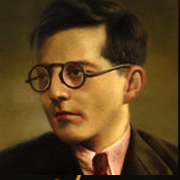

Russian composer Dmitry Shostakovich (1906–1985) wrote his 24 Preludes and Fugues between October 1950 and February 1951. This was a time when the style of abstract compositions such as these were not just an undesirable, but also a dangerous venture, since it was required by the Zhdanov Decree of 1948 that ‘intellectual’ music of this type should be replaced by music that conformed to Soviet party diktats. This made Shostakovich’s concert and recital music unperformable.

Ironically, the ban allowed Shostakovich the space to undertake some extensive travel, including to Leipzig in 1950 for the Bach centennial celebrations. There, he was impressed by the artistry of one of the performers, pianist Tatyana Nikolayeva, who became the catalyst for his 24 Preludes and Fugues. She gave the first complete performance of the set in December 1952. Here’s the Prelude No. 13 in F sharp major.

Finally, to The Bad-Tempered Electronic Keyboard: 24 Preludes and Fugues by Anthony Burgess, the noted British author and composer. He wrote the set in 1985 to celebrate the 300th anniversary of J.S. Bach’s birth; the title pays ironic homage to Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, the source of the first extract in this blog. Throughout his set, Burgess oscillates between the classicism of Bach and the modernity of Shostakovich. Here’s his Prelude and Fugue in G flat major.