From the Naxos Blog: Mere trifles?

August 19, 2022Labelling Beethoven’s Für Elise a mere trifle might appear insulting to such a household name and piano solo favourite. But that’s exactly what his Bagatelle No. 25 in A minor is, ‘une bagatelle’ translating from the French as ‘a trifling matter’. This blog examines the recipes composers have used for a selection of bagatelles over the eras. As might be expected, many ’trifles’ are done and dusted in a matter of a minute or two. But not all.

My first example (and one of the shortest) is by Bohuslav Martinů, who was born in what is now the Czech Republic, subsequently moved to Paris in 1923, and from there to the US in 1940 with the approach of the German armies. It’s subtitled Morceau facile and was written in New York in 1949.

If you think a piece couldn’t get any shorter than that, listen on to the first movement of Hungarian composer Sándor Balassa’s (1925–2021) Bagatelles and Sequences, Op. 17, which mischievously ends with a cherry on the top. Or maybe a raspberry. He once wrote a Gallop in 3/4 time, justifying it as being about a three-legged horse! Written c. 1953 at the start of his university studies, the Op. 17 is among Balassa’s earliest published pieces when—as he put it himself—he was just starting to learn the alphabet of composition.

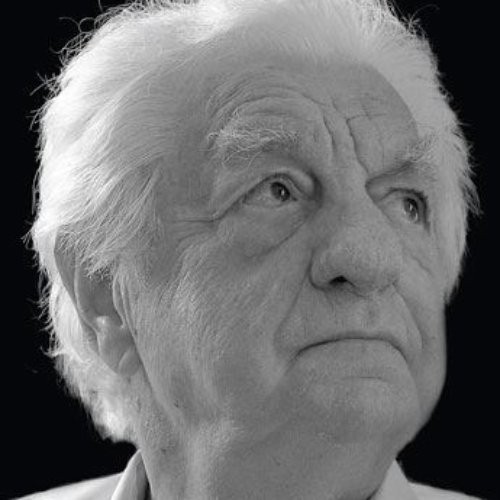

Now to music by Nicolai Kapustin (1937–2020), whose

“At last, something really new.” That’s how Ferrucio Busoni described Béla Bartók’s Fourteen Bagatelles, Op. 6 which Bartók composed in 1908. This was a time when he had been spurned in love by the violinist Stefi Geyer; perhaps they helped him transform his desolation at her rejection into something more positive. The bagatelles display, in embryonic form, many of the qualities associated with Bartók’s mature style. The final one in the set, however, seems to go off at a tangent. Compare and contrast No. 3 with No. 14, subtitled Valse (M’amie qui danse…)

In slight contrast to the solo piano extracts heard so far, I’ve turned to a piece for violin and piano by Francis Poulenc. It’s a transcription of the Bagatelle from his cantata Le bal masqué. To say that the violin wasn’t Poulenc’s favourite instrument would be an understatement. “Nothing is further from human breath than the bow-stroke”, he once exclaimed to the music critic Claude Tostand. His chamber music was mostly devoted to wind instruments and piano, and rarely ventured into the less familiar medium of string instruments. He gave us only one sonata for violin and piano, plus one for cello and piano. As for his string quartet—“the disgrace of my life”—it ended up down a drain in the Place Péreire one day in 1947. Here, however, is the violin and piano transcription of the Bagatelle referred to above.

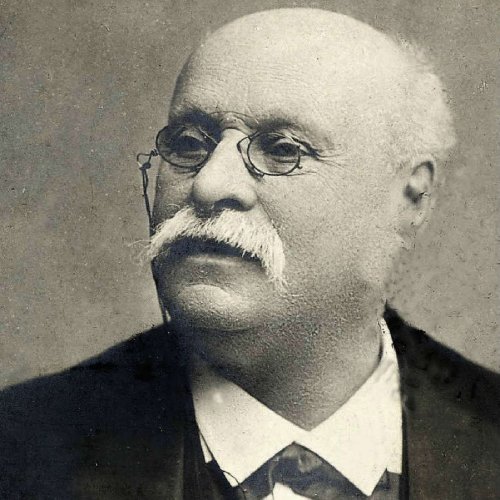

Émile Waldteufel (1837–1915) eventually established himself in Paris and London as a leading composer of dance music—the French equivalent of Johann Strauss. While a student at the Paris Conservatoire, his family’s dance orchestra was becoming one of the best-known in the city, increasingly in demand for society balls; from 1867 the Waldteufel orchestra played at Napoleon III’s magnificent court balls at the Tuileries. Yet Émile’s dances remained known by a relatively limited audience until he was almost forty. In 1874 he happened to be performing at an event attended by the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, who complimented Waldteufel on his music and agreed to help launch his works in London.

The result was a long-term publishing contract with the London firm of Hopwood & Crew. Avenues opened up and Waldteufel went on to find worldwide fame. Though waltzes were his forte, his contract with Hopwood & Crew also expected him to supply polkas and other small pieces. One of his last for the publisher was the Bagatelle, Polka which we end with today. So, dig into your last piece of trifle, but note that you probably won’t need any extra sugar on Waldteufel’s confection.