From the Naxos Blog: Musical discoveries A–E

April 16, 2021This is the start of a 5-part series highlighting the distinctly engaging music of less well-known composers. I’ve selected their names alphabetically, and this edition’s tranche features composers with surnames beginning respectively with the letters A, B, C, D and E.

First in the spotlight is the Georgian composer Vaja Azarashvili. Born in 1936, he has been described as the ‘lyricist’ of Georgian musical culture. Like many composers of his generation, his music shows the influence of the titans of Russian music, Sergey Prokofiev and Dmitri Shostakovich; but it also evidences his own distinctive musical language that’s rooted in free improvisation and Georgian modality. Azarashvili has written music for cello throughout his life, so I’ve chosen music featuring that instrument: his Cello Sonata No. 2, written for and dedicated to Eldar Issakadze who premiered the work in Tbilisi in 1976. The energetic Allegro finale develops into a furious climax before gradually drawing to a quiet close and disappearing into the ether.

João Domingos Bomtempo was born in Lisbon in 1771. Unlike most Portuguese composers of the eighteenth century who went to Italy to pursue their musical studies, Bomtempo established himself in Paris in 1801, and soon developed a brilliant career as a pianist and composer. A friend of Muzio Clementi, he absorbed the new pianistic style of this Italian composer, pedagogue and music publisher. After the premiere of his First Symphony in Paris in 1809, he established himself in London, where Clementi became his publisher.

Bomtempo’s First Symphony shows the influence of Haydn and Mozart and is scored for strings, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns and timpani. The oldest existing copy of the full orchestral score is in the handwriting of a copyist. Curiously, it has no trumpets. Since the timpani part is independent of that of the horns, and since the symphonies which directly influenced Bomtempo did not use timpani without trumpets, the conductor on our recording—Álvaro Cassuto—added two trumpets to the timpani part. Here is the fourth and final movement.

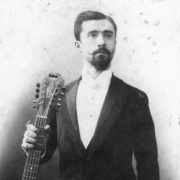

We turn to music on a much smaller scale now with a piece by Raffaele Calace. Born in Naples in 1863, he has arguably become the single most important figure in the history of the mandolin. His family were established mandolin and guitar makers. Raffaele excelled both as a business man, performer and composer, who set about putting the mandolin into what he considered to be its rightful place amongst the musical circles of the world. A player of incredible virtuosity, he took mandolin techniques to new levels and was greatly admired for his expressive and beautiful playing. We can hear his Danza dei nani (Dance of the Elves), a lighthearted show-piece which demonstrates the instrument’s agility.

Born in 1929, the Belgian conductor and composer Frédéric Devreese died in Brussels last year at the age of 91. The son of the violinist, composer and conductor Godfried Devreese, Frédéric first studied composition with his father, then with Marcel Poot and, in Rome, with Pizzetti; he also studied conducting with Hans Swarowsky in Vienna.

He wrote the first three of his four piano concertos while he was still quite young, but they already revealed the composer’s great personality, creativity and originality. His First Piano Concerto earned him the Prize of the City of Ostend when he was only 19, and his later concertos remain eclectic in idiom but immediately accessible. I’ve chosen the exciting last movement from his Third Piano Concerto to present his music. The relationship between the melodic lines and the part-writing is quite complex: counter-movements and polyphony—such as canons—come and go, while the exchanges between piano and orchestra produce quick-tempered dialogues of witty motifs which cut each other short. Our recording features Frédéric Devreese himself conducting the work.

Our final alphabetical appearance is by Joachim Nikolas Eggert (1779–1813). One of the more forward-looking Swedish composers and conductors of his age, Eggert died before achieving wider European recognition and has remained neglected ever since. He didn’t have the easiest of times progressing his education and subsequent career, at one point even contemplating giving up music completely.

En route to St Petersburg to join the Russian Imperial Chapel, he fell ill in Stockholm, where he was offered a position as a violinist. Over the next few years his reputation as a composer spread and in 1807 he was appointed Kapellmeister and a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music. When the new monarch, Carl XIII, reorganised the establishment with the intent on returning it to its former glory in 1810, Eggert was designated to go on a grand tour. Unfortunately he fell fatally ill and died on 14 April 1813 at the home of one of his students who lived in the Swedish countryside.

Written in 1812, his Fourth Symphony clearly reflects the military backdrop to the political unrest of the times. Here’s the finale.