From the Naxos Blog: Scoring their centuries

September 16, 2022When a composer’s work is marked as his or her Opus 100, it surely marks a milestone in their development. Some composers didn’t make it that far, of course, leaving us wondering what might have been, had they lived long enough or enjoyed circumstances that better facilitated a freedom to compose. Chopin falls into another category: he died when he was 39, leaving us with Op. 65 as his last work to be numbered in that way; he completed many others, but they remained unpublished. Some composers aren’t documented by use of the ‘opus system’, but we can cheat in their cases by spotlighting the ‘100’ used in their particular classification system: Mozart’s K.100 (Köchel), for example, or J. S. Bach’s BWV 100 (Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis) or Liszt’s S.100 (Searle).

So, here’s a lucky dip selection of six works from the catalogue’s century markers. Do they reflect a milestone maturity? I’ll leave it to you to decide.

I’m opening with a song by Russian composer Dmitry Shostakovich (1906–1975), one of his Spanish Songs Op. 100 which he wrote in 1956 for mezzo-soprano and piano. Titled Little Stars and based on an old Spanish folk song, the text translates as follows:

A young man hurries under the cypresses on the seashore, holding his guitar, to meet his sweetheart and to teach her songs. He requires kisses as reward for his lessons and next morning she remembers everything except for notes. It is such a shame not to be able to restart from the beginning, because it is daytime and the stars don’t shine. By night, he teaches his beloved the names of all shining stars and gets one kiss for every name. It is strange—she learns everything easily, but not the names of the stars.

Compare that vignette with the Op. 100 by Shostakovich’s contemporary, the Ukrainian-born Sergey Prokofiev (1891–1953). Educated in Russia, Prokofiev subsequently lived in America and Paris before returning to Russia in 1936. Having previously escaped censure of his music by the Russian regime, this time round he wasn’t so fortunate. In 1948 Prokofiev’s name was openly joined with that of Shostakovich (a long-term sufferer of Stalin’s controlling diktats) in an even more explicit condemnation of formalism, with particular reference to his opera War and Peace. Prokofiev died in 1953 on the same day as Joseph Stalin, and so never benefited from the subsequent relaxation in official policy to the arts.

Written in 1944, Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony, Op. 100 (he wrote seven altogether) is one of his greatest and most complete symphonic statements. At its premiere he himself called it “a symphony of the grandeur of the human spirit”. Here’s the concluding section of the work’s finale.

From eastern to central Europe now and music from the 19th century. The first is by Antoine Reicha (1770–1836), who was born in Prague but subsequently moved to Bonn (where as a teenager he met and befriended Beethoven), thence to Hamburg, Paris, Vienna and finally back to Paris (the constant moves arising from Napoleon’s military manoeuvres). In Paris he became a well respected figure in the French musical establishment, attracting pupils such as Berlioz, Liszt, Franck and Gounod. Reicha promoted the relatively new combination of flute, oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon in his 24 compositions for the ensemble. John Sainsbury, a critic from the time, commented in 1825: “The effect created by the extraordinary combinations of apparently opposite-toned instruments, added to Reicha’s vigorous style of writing and judicious arrangement, have rendered these quintets the admiration of the musical world.”

Reicha’s Six Quintets Op. 100 were published a year before Sainsbury’s review. Here’s the third movement from the fifth quintet in the set. Note the use of a strange fanfare-like motif in the central section.

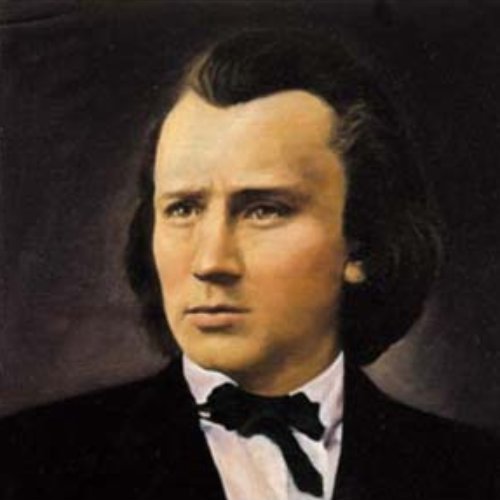

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) completed the second of his three violin sonatas in 1886 while on holiday in Switzerland. First performed in December of that same year in Vienna, it was published as Violin Sonata No. 2 in A major, Op. 100. Brahms had begun his professional career as a piano accompanist to better-known artists, and it was in this capacity that he made the acquaintance of the renowned violinist Joseph Joachim. Their association developed into a friendship that lasted the length of their adult lives and resulted in the composition of Brahms’ Violin Concerto, the Double Concerto for violin and cello, and the three violin sonatas. The latter were written at the height of Brahms’ maturity and contain some of his most intense and beautiful music. I’ve selected the second sonata’s second movement.

Across The Pond to the US now, where Antonín Dvořák served as director of the National Conservatory of Music of America from 1892 to 1895. It was only a matter of months that separated the composition of his mighty Symphony No. 9, ’From the New World’, Op. 95 and his self-effacing Violin Sonatina in G major, Op. 100, which he completed in the last two weeks of November 1893. Intended for performance by his own children, Ottilie and Antonín, it exudes nostalgia for his native Czechoslovakia while at the same time drawing on new musical influences from his American backdrop. Here’s the sonatina’s last movement that carries echoes of Dvořák’s ‘New World Symphony’, Op. 95 and his String Quartet Op. 96, ’The American Quartet’.

Finally to the Cassation (Serenade) in D major, K. 100 by Mozart (1756–1791). The exact derivation of the word ‘cassation’ can’t be confirmed; there are a number of possible roots from which it was adopted. The word is generally applied, however, to compositions otherwise known as serenades or divertimenti, works in a lighter style in a series of short movements. Mozart’s K. 100 was probably written in Salzburg during the summer months when the end of the academic year was marked by outdoor performances in front of buildings occupied by either nobility or academics. I’ve chosen the first of the eight short movements that make up Mozart’s K. 100. As to whether or not you think it marks a milestone of maturity, do remember that Mozart was only 13 years old when he wrote it in 1769!