From the Naxos Blog: Warpaths

July 15, 2022It’s maybe too convenient to restrict references to war to big anniversary dates, so this blog presents a small selection of musical works that paint the subject of conflict in tuneful reminders of how wearisome and worthless the daily pursuit is.

There’s no place like home, as they say, so I’m going to start with a short extract from American composer James Hartway’s Scenes from a Marriage. In 1993 he was interviewed on radio and was asked “How does someone commission you to write a piece?” Hartmann replied: “Call me and ask.” One of the listeners did just that, revealing that he had married one of Hartway’s former students and wanted to give her a special present for her fortieth birthday. The result was a short 4-movement suite, Scenes from a Marriage, scored for one piano four hands, as a sort of marital duet. The second movement is titled In conflict, with the players contradicting and interrupting each other.

Now to an old conflict with a modern resonance, as found in Tchaikovsky’s opera Mazeppa (1883), the plot of which was based on Pushkin’s narrative poem Poltava. Mazeppa (1640–1709) was a military commander of the Ukrainian Cossacks. The opera’s narrative features plenty of persecution, betrayal, vengeful murder … you get the picture. Act 3 is introduced by music representing the Battle of Poltava. By this stage, Mazeppa has resolved to challenge Russia’s Tsar Peter the Great by siding with King Charles the XII of Sweden in his aim to establish Ukraine’s independence. The battle sees Mazeppa and the Swedes defeated, with the Act 3 tableau of the conflict referencing the hymn of Peter’s victorious army.

For another spotlight on the vanquished, I’ve chosen one of Richard Danielpour’s War Songs, which the American composer introduces as follows:

“The motivating force for this cycle … originated from seeing a series of photographs printed in The New York Times of all the young men and women who had been killed in the Iraq War … Nowadays, we understand war basically through motion pictures and mass media, and we’re shielded from truly understanding the hellish reality of war. War Songs is my effort to shine a light on the real brutality of war and the effect it has on those surviving the loss of loved ones.”

Commissioned in 2008, War Songs originally set seven Civil War poems by Walt Whitman for voice and piano; Danielpour subsequently orchestrated four of them, the first of which is Hush’d Be the Camps Today.

Hush’d be the camps to-day,

And soldiers, let us drape our war-worn weapons;

And each, with musing soul retire, to celebrate,

Our dear commander’s death.

No more for him life’s stormy conflicts;

Nor victory, nor defeat — No more time’s dark events,

Charging like ceaseless clouds across the sky.

But Sing, poet, in our name;

Sing of the love we bore him — because you,

dweller in camps, know it truly

Sing, to the lower’d coffin there;

Sing with the shovel’d clods that fill the grave — a verse,

For the heavy hearts of soldiers.

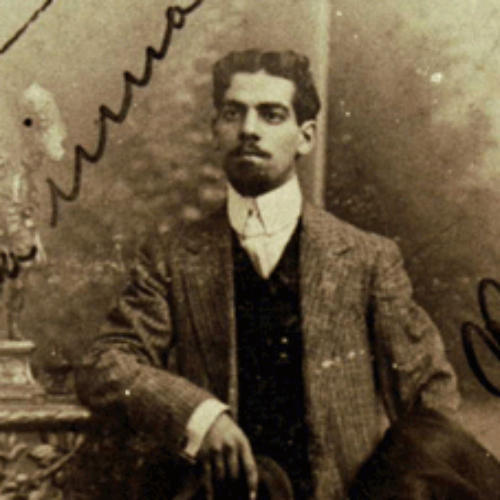

We move from North to South America and music by the Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887–1959). Brazil had a minor involvement in the First World War, but the country was transformed by the impact of the conflict. It initially declared itself neutral, but the torpedo attack on Brazilian ships by German submarines in 1917 provoked national outrage, obliging the government to align itself against the Germanic coalition, by patrolling the south Atlantic. Coffee, Brazil’s only export product, was no longer deemed an essential commodity during the conflict, and this forced the country to diversify its economy and begin to establish an industrial infrastructure, which led to prosperity in the 1920s.

Villa-Lobos’ ‘War’ and ‘Victory’ Symphonies (respectively the Third and Fourth) were commissioned by the Brazilian government in 1919. Using very large orchestral forces, and conveying the composer’s feelings about the conflict with no sense of triumphalism, the two symphonies display unusual and evocative effects, such as the collage of fragments of the Brazilian national anthem and La Marseillaise in the ‘Battle’ movement of the Third Symphony. Included in that government commission was a Fifth Symphony, ‘Peace’. Ominously, if indeed the symphony was completed, it was never performed and the score is lost.

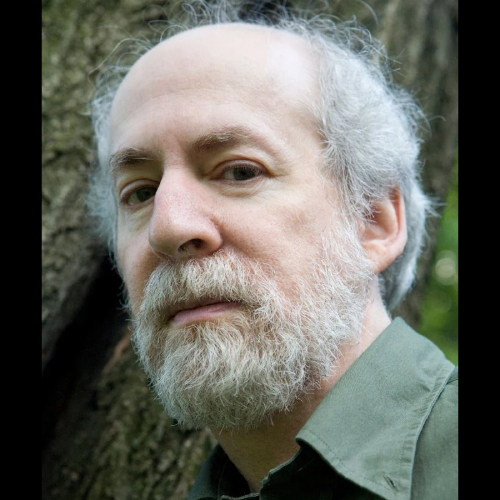

Haskell Small’s Lullaby of War occupies contrasting ends of the emotional spectrum as (in the composer’s words) “both an expression of outrage at our perpetual rationalizations for making war and an offering of compassion for its victims.” It’s a six-movement work for piano and narrator, the last of which is titled Guernica Pantoum, a setting of text by Paula Tatarunis that gives expression to Picasso’s famously powerful anti-war painting, as in these opening stanzas:

Of the eighteen eyes in Guernica, sixteen are open.

Of its nine mouths, eight gape and cry.

There is a bull, a bird, a horse, one child broken,

one mother grieving; elsewhere, others fall, flee, watch, die.

Not nine mouths, but eight gape and cry

with impeccable lips, palates, tongues, teeth.

One woman grieves; elsewhere, others fall, flee, watch, or die

while lance and flame menace their raw breath.

With impeccable lips, palates, tongues, and teeth

eight mouths siren terrible laments

until lance and flame, transfixing their raw breath,

become the pivot of a deathward dance.

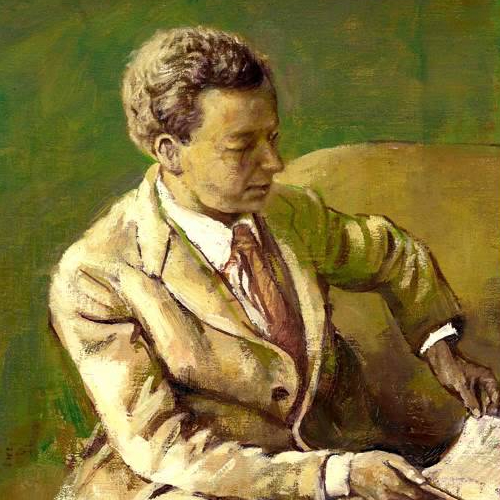

In 1961 the English composer Benjamin Britten (1913–1976) was commissioned to write a work as part of the celebrations marking the re-consecration of Coventry Cathedral, which had been virtually destroyed by bombing in the Second World War but was subsequently rebuilt. Britten’s work makes use of disparate groups of performers. The full orchestra, chorus and soprano soloist are given the text of the Latin Requiem Mass, while the male soloists and chamber orchestra offer, in juxtaposition, moving and closely related poems by the English poet and soldier Wilfred Owen (1893–1918). The boys choir and organ provide a further role and level of experience.

We end this blog with the opening of the Dies irae (Day of Wrath) section where the great sacred hymn describing the terrors of the world leads to the baritone’s singing of Owen’s secular poem Bugles sang, sadd’ning the evening air, a counterpart to the last trumpet of the Dies irae, and a poignant meeting of the hells of both church and state.

Bugles sang, saddening the evening air,

And bugles answered, sorrowful to hear.

Voices of boys were by the river-side.

Sleep mothered them; and left the twilight sad.

The shadow of the morrow weighed on men.

Voices of old despondency resigned,

Bowed by the shadow of the morrow, slept.